The Mexican War of 1848 is largely forgotten today. Its a conflict that was pivotal for ascent of the United States on the world stage. But largely been overshadowed by the American Civil War and the Gilded Age.

But Mexico's loss is often overlooked.

Its legacy was not just a redrawn border, but a recalibration of regional power. The United States emerged as a continental force, setting its foundation as a future great power in the late 19th and 20th Century. Mexico, shorn of half its territory, was relegated to a regional player in North American politics.

One nation gained regional dominance to project power beyond its continent, while the other accepted the limits of a secondary power. A structural reality that still defines the hemisphere. Wars fade from memory, but their consequences do not.

Its easier to focus on the battles of the Mexican War, and there’s lots of great resources for it. But here, I’ll talk about the geopolitical consequences of Mexico’s loss.

I. A Vast Continental Inheritance (1821–1846)

When Mexico broke from Spain in 1821, it did not emerge as a battered colony. It emerged positioned for great potential. Its territory stretched from the Pacific coast of Alta California to the Gulf of Mexico, from the jungles of Chiapas to the snow-fed peaks of the Oregon borderlands.

It controlled two oceans, thousands of miles of frontier, and some of the richest mining regions in the hemisphere. The state inherited not only space, but material potential: silver veins, river basins, forests, ports, and the skeletal infrastructure of Spanish imperial rule.

The most promising parts of this inheritance lay in the north. Texas, New Mexico, and Alta California were underpopulated but resource-rich. Texas contained cotton-growing river bottoms and open grazing land that linked naturally into the Mississippi trade system. New Mexico, perched between mountain and desert, offered a corridor to the interior and a natural defensive depth against any overland invasion. California, with its harbors at San Diego, Monterey, and San Francisco, and with its fertile inland valleys, was a Pacific fulcrum awaiting development.

On maps, the republic appeared to possess everything required for continental command. But that possession was paper-thin.

In 1820, Texas had fewer than 4,000 Mexican settlers. Alta California, over a thousand miles from the capital, held barely 3,200 Spanish-speaking civilians. New Mexico’s towns operated as isolated fortresses, sustained by barter economies and supply trains that moved at the speed of mules. Roads washed out in rainy seasons. Presidios went months without resupply. Authority radiated weakly from the center, diluted by distance, terrain, and tribal resistance.

State presence was outpaced by foreign migration. In Texas, Anglo-American settlers arrived in numbers far exceeding what the government could assimilate or repel. Comanche and Apache raids made overland communication dangerous. Mexico had inherited land, but not settlers; obligations, but not revenues; claims, but not capacity.

But holding a continent requires more than titles. It demands settlers, money, and soldiers. Mexico’s ledgers showed a surplus of titles, and a fatal deficit in the rest.

The geography itself compounded the challenge. While central Mexico benefited from a stable climate and dense population, the north veered between extremes: drought-ridden plains, unbroken deserts, and mountain ranges that turned commerce into siegecraft. Even where land was fertile, development required irrigation, capital, and peace—none of which the frontier guaranteed.

Lucas Alamán, one of the few statesmen to grasp the scale of the challenge, warned:

“In dangerous matters of government one instant lost is going to determine its fate.”

His warning was not about foreign invasion, but the inertia of neglect.

By the 1840s, Mexico remained a continental state in form. But the strategic heart of its domain. the northern frontier, was unstable, lightly held, and increasingly ungovernable. The republic had inherited the shell of an empire. Whether it could hold it was no longer a legal question. It was becoming a geographic one.

But the fault lines had already opened. It would take only a single war to break the illusion.

2. The Mexican-American War (1846–1848): The Fallen Eagle

The Mexican-American War did not rise from just provocation, but also from imbalance. It revealed what had been concealed: that Mexico’s inheritance from Spain rested on paper, not power.

José María Tornel had warned as early as 1837 in a pamphlet:

La pérdida de Tejas acarrearía inevitablemente la del Nuevo México y de las Californias; y poco a poco se iría menoscabando nuestro territorio, hasta quedar reducidos a una expresión insignificante

The loss of Texas will inevitably result in the loss of New Mexico and the Californias; and little by little our territory will be diminished, until we are reduced to an insignificant remnant.

The Texas Revolution and US Annexation turned that warning into writing on a grave stone.

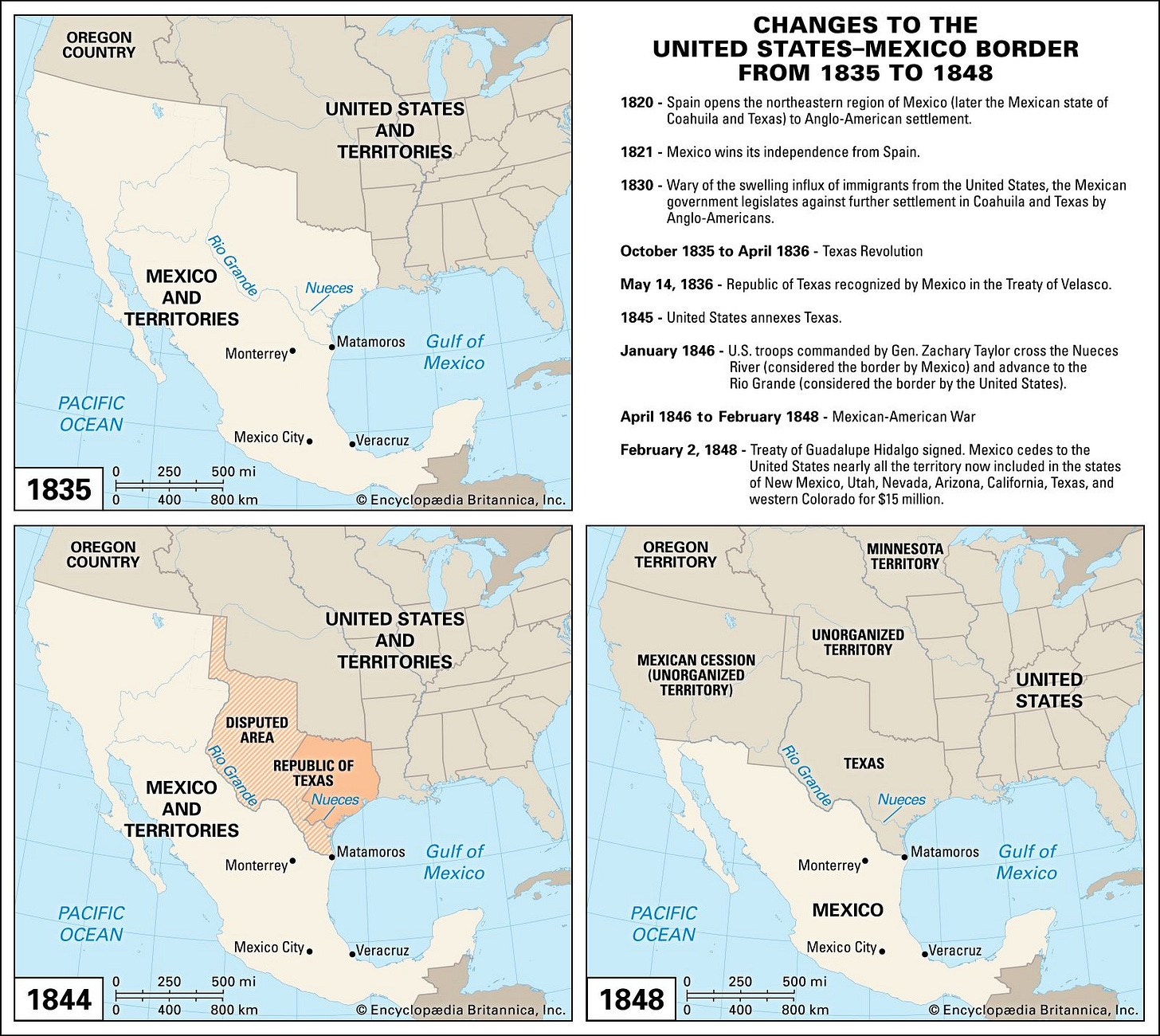

By 1845, the United States had annexed Texas and pushed its border to the Rio Grande. Mexico, fractured by rebellion and debt, mobilized disorganized militias against a professional U.S. army.

When war broke in 1846, the outcome was preordained. American forces under General Zachary Taylor crossed the disputed zone with 4,000 men. Mexico’s troops- unpaid, underfed, and unequipped - offered resistance but lacked cohesion, logistics, and military organization.

The asymmetry was structural. The United States deployed under 80,000 troops but with industrial logistics, naval supremacy, and unified command. Mexico’s army, nominally of similar size, suffered 30% desertion rates and relied on 18th-century artillery.

In the north, Kearny took Santa Fe without firing a shot. In the west, Sloat seized California’s ports while American settlers rose in revolt. In the east, Winfield Scott landed at Veracruz, broke through Cerro Gordo, and captured Mexico City in under six months. With relatively very little resistance - territory could be controlled by Mexico, but not held in practice.

Interim President Manuel de la Peña y Peña, who would sign the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, acknowledged the reality:

“Our only hope would not be for victory, simply the avoidance of certain defeat.”

His words marked not only a surrender, but recognition of structural collapse.

Peña y Peña understood the cruel arithmetic of geopolitics: when resistance is impossible, surrender becomes damage control.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo cost Mexico over 930,000 square miles—nearly half its national territory. In exchange came $15 million and token debt relief. But the real price lay in what could no longer be defended, developed, or claimed.

The ceded lands held the levers of future power—resources, ports, river systems, and demographic corridors that would define the coming century. What Mexico lost was not only space—it was leverage. Each province surrendered meant one less axis of sovereignty, one less option on the strategic board.

The military consequences were immediate. National defense spending collapsed by 40% within a decade. Northern garrisons disbanded. By the 1850s, Mexico fielded fewer than 12,000 regular troops—scattered, poorly supplied, and often loyal to local caudillos rather than the state.

The psychological rupture was deeper. Before the war, Mexico imagined itself as a continental state. After it, that identity collapsed. Melchor Ocampo, reflecting on the nation's plight, urged continued resistance against the invaders and opposed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, believing it compromised Mexico's sovereignty and future.

What followed defeat was an national reorientation. Expansion gave way to endurance. The vision of a sovereign empire faded into the reality of survival.

The war altered the course of Mexico’s strategic future. It transferred not only land, but surplus, mobility, and maritime access. It stripped Mexico of its external leverage and internal cohesion. What had once been territorial inheritance became irrevocable loss.

To grasp the scale of rupture, one must begin with what the map no longer held.

3. Geography as Destiny: How the Mexican War Shattered Mexican Ambition

In the aftermath of 1848, Mexico faced a brutal geographic reckoning - with massive political and economic effects. The war had redrawn more than borders—it had severed the arteries through which a continental power breathes.

What remained was a brittle core: mountains without depth, coasts without harbors, rivers that flowed inward but led nowhere.

The republic’s geography, once the canvas of ambition, became a map of constraint. Each lost region—Texas, New Mexico, Alta California—had offered more than land. They held surplus, scale, access, and time. Their absence did not simply shrink Mexico. It redefined what Mexico could be.

Let’s look at each region by region.

1. Texas: The Loss of Agriculture and Transport

Among the territories Mexico inherited after independence, Texas stood apart.

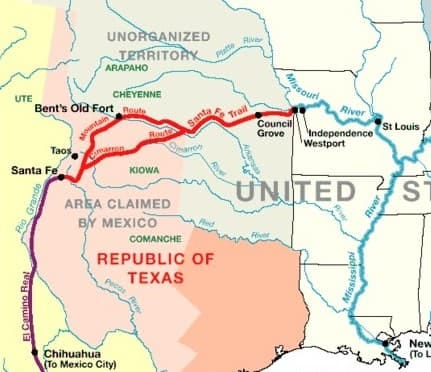

Its geography aligned with the commercial and agricultural rhythms of the broader North American interior. Rich soils, reliable rivers, and consistent rainfall made it the most naturally integrated frontier Mexico possessed—closer in function to Mississippi than to Mexico City.

The Brazos, Trinity, Colorado, and Red Rivers offered over 2,000 miles of internal navigation, linking the interior to Gulf ports. Eastern Texas received between 35 and 50 inches of rainfall annually—far more than most of northern or central Mexico. Its black Alfisol soils supported cotton, corn, and cattle at volumes rivaling the American South. By the 1830s, Texian planters were producing harvests comparable to those in Mississippi and Alabama.

Much of Mexico offered no such promise. North of the central plateau, rivers dried before reaching the sea. Rainfall came sporadically, agriculture required costly irrigation, and transport moved at the pace of mule trains. In a country shaped by elevation and drought, Texas offered an opening - one of the few regions where geography could scale to a prosperous future.

The loss of Texas closed off that future. By 1860, U.S. cotton exports had reached $191 million, more than twice the value of Mexico’s entire export economy. The wealth that could have financed foundries, railroads, and financial institutions instead flowed into New Orleans, Liverpool, and Manchester. What remained behind was an economy anchored to subsistence, fragmented by terrain, and disconnected from continental commerce.

Texas’s rivers, which might have integrated frontier towns into a national system, now carried American goods downstream. Its prairies, once mapped as Mexican, became engines of another republic’s growth. Geography had offered Mexico a strategic corridor into the interior of North America.

Its removal left the republic cut off—trapped behind its mountains, watching the arteries of power flow elsewhere.

2. New Mexico: The Collapse of Strategic Depth

Mexico's natural borders were never kind. The Sierra Madre ranges—Oriental and Occidental, fragmented more than they protected. The Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts, stretching endlessly under burning skies, divided north from south, east from west, without ever providing true defensive bastions.

Moving troops or goods across Mexico’s north required endurance against terrain as much as any human foe: mule trains moving barely 12–15 miles per day, desert caravans forced to carry twice their weight in water.

New Mexico was the strategic keystone that compensated for these weaknesses. Though its arable land was minimal (only around 2% of its total territory) its deserts, mountains, and passes served as natural kill zones and barriers. The Jornada del Muerto, a searing 90-mile stretch of desert, could obliterate unprepared armies. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains controlled the key passes eastward toward the plains. Fortified settlements like Santa Fe and Albuquerque operated not only colonial outposts, but as strategic sentinels, gates regulating any north-south or east-west movement.

By retaining New Mexico, Mexico preserved an early warning system against Anglo-American advance. Any invasion would have to bleed itself across hundreds of miles of barren desert and treacherous mountains before reaching the Mexican interior or Alta California. A Mexico anchored on New Mexico’s geography could have bought precious months to mobilize, negotiate, or entrench. And linked the vast resources of Texas, California, and the Rockies.

When New Mexico fell, Mexico’s strategic breathing space collapsed.

The doors swung open onto the heartland itself. The American frontier, backed by mass migration, economic scale, and military-industrial development, could now roll southward almost unchecked.

Between 1850 and 1870, the American population in the former Mexican territories would quadruple, while Mexico’s northern population stagnated, unable to attract settlers to its increasingly vulnerable lands. As time went on, the US was able to do what Mexico could not - hold the territory using both settlement and military power projection.

Without New Mexico, Mexico’s internal north fell into chaos. While Apache and Comanche raiders had ranged past the Rio Grande, forts and settlements in both Texas and New Mexico that controlled water sources and grazing land helped limit, and even interdict their movement.

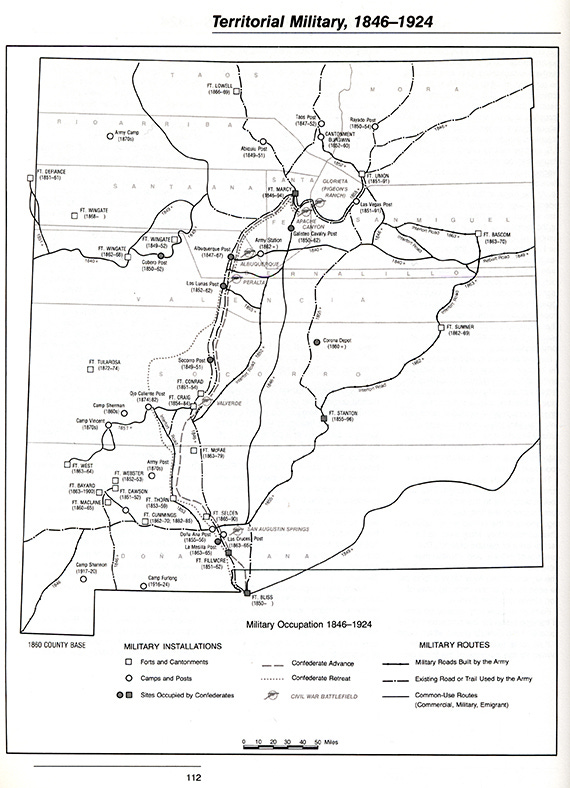

This echoed throughout the 20th Century. It is no accident that more than half a century later that the 1917 US Punitive Expedition crossed into Mexico from Columbus, New Mexico. Or that until present day, the US military retains a significant presence in the state and bordering states.

The frontier that could have been Mexico’s shield became its vulnerability. One it would discover not just in the 19th Century, but in the 20th as the US solidified its political and military dominance over North America.

3. Alta California: The Aborted Rise to Pacific Power

Alta California was the last domain through which Mexico might have shaped an emerging Pacific order. Even without Texas or New Mexico, controlling Alta California was a rough jewel in the Mexican Republic’s crown - full of fertile lands, natural harbors, resources, and defensible borders. All of which were undeveloped, under utilized, and barely surveyed.

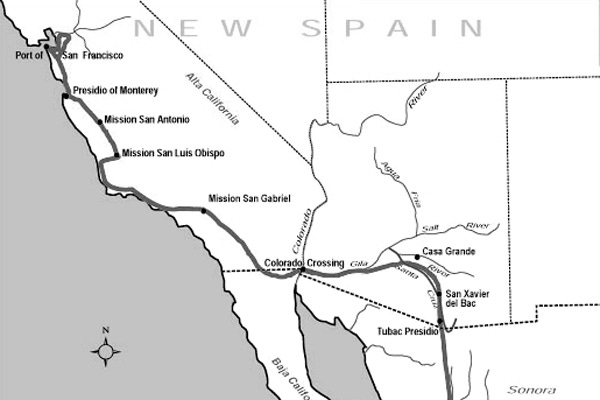

While the rest of the Mexican Republic remained tied to the decaying arteries of Spanish Atlantic trade, California faced west—toward the shipping lanes of Asia, the migration routes of North America, and the new commercial geography of empire.

Its geography aligned with strategic ambition. The Central Valley stretched for 450 miles, flanked by the Sierra Nevada and Coast Range, irrigated by snowmelt and Mediterranean rains. It held over 20,000 square miles of arable land, capable (then as now) of supporting millions.

The coast offered three natural harbors, San Francisco, Monterey, and San Diego, deep enough to anchor fleets, calm enough to sustain commerce, and positioned at critical junctures between hemispheres.

San Francisco Bay, provided not just commercial utility but a strategic advantage. It was the best natural harbor on the Pacific coast—a maritime fulcrum capable of turning the movement of goods, men, and power. Deep enough to host fleets of merchant ships, but also naval fleets. Whoever controlled it could project influence from East Asia to South America. San Diego, further south, offered a staging ground for naval logistics across the hemisphere. California was not a peripheral possession.

Its mineral resources reinforced that position. Gold, discovered at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848, only days before the treaty was signed, transformed California into a magnet for labor, capital, and shipping. Within a year, over 300,000 migrants arrived. But gold was only the opening act. Copper, quicksilver, and timber—critical to 19th-century industry—and oil, discovered soon after, made the territory central to any state seeking industrial scale and maritime depth. By 1852, California’s economy exceeded that of the rest of Mexico combined.

Mexico exercised very limited control over it during its rule. The territory remained under-defended, underpopulated, and administratively peripheral. Yet its long run strategic potential was unmistakable, when the United States began to develop it. In surrendering Alta California, the republic did more than lose land. It relinquished leverage that flowed from the Pacific: trade flows, technological revolutions, and demographic movements that would define the next century.

A nation that cannot populate or administer its borderlands will inevitably govern someone else's frontier. Territorial claims that outstrip institutional frameworks to bind them is an invitation to invaders.

The loss locked Mexico behind barren coastlines. It remained a Pacific nation in cartography, but not in power. Its position in the Pacific world was vacated by defeat in the Mexican War. Vast territories full of resources that could’ve given Mexico geopolitical leverage to stand on the world stage were lost. The loss of Alta California was more devastating than the loss of Texas or New Mexico combined.

California was the last lever Mexico might have pulled to escape its continental prison. When it broke, so too did any claim to influence beyond its own eroded borders.

Already weakened by war, debt, and political instability, the Mexican state could not reconstitute the capacity to engage outward. The loss of Alta California reduced not only its territorial range, but its position in the emerging 19th Century industrial order.

4. Reaction and Internal Fragmentation (1848–1870s)

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo removed more than land. It dissolved the strategic foundation that had supported national coherence. With the loss of Texas, New Mexico, and Alta California, Mexico surrendered the outer perimeter that had once absorbed pressure, projected ambition, and justified central authority. The map contracted. So did the republic’s ability to function as a unified state.

Before the war, political factions—monarchist, federalist, centralist—competed over structure but still assumed the full territory would remain Mexican. Leaders like Iturbide and Santa Anna treated the frontier as a delayed asset rather than a contested zone. That belief gave internal politics a direction. Expansion offered an answer to disorder. When the frontier was severed, the internal system lost its outlet.

The mathematics of fragmentation follow certain patterns. As national territory shrinks, the number of would-be rulers multiplies in inverse proportion.

Centrifugal pressures intensified. Regional caudillos, including Juan Álvarez in Guerrero and Santiago Vidaurri in Nuevo León, consolidated power independent of the capital. The national army, weakened by defeat and fiscal collapse, declined to under 12,000 troops by the 1850s. Units were unpaid, poorly equipped, and loyal to local commanders. Garrison officers governed entire provinces. Military revolts replaced legal succession. Between 1848 and 1876, over 50 governments came and went—each one less capable of restoring authority than the last.

Constitutions followed the same pattern. Five foundational charters were enacted between 1821 and 1857, each claiming to resolve crisis, each discarded under pressure. Federalism and centralism served shifting factions rather than stable principles.

Foreign creditors intervened. Mexico’s public debt surged after the war. In 1861, default invited British, Spanish, and French troops to Veracruz to pressure repayment. Even after the British and Spanish left, the French smelling a new continental foothold, advanced inland. Within months, a European expedition imposed Maximilian, a Hapsburg prince from Austria, on the Mexican throne. A foreign emperor installed over a fragmented republic that could no longer dictate its own terms.

This was the result of the long changes after the defeat of 1848 - a geopolitical rupture, followed by a political reckoning that unfolded over the next 50 years after the defeat. Consequences are rarely in short time windows in geopolitics, despite modern obsession, but in reality unfold under longer time windows.

These events unfolded not as isolated misfortunes but as structural consequences. The republic had lost its geographic depth, its economic margin, and its sense of direction. What remained was a compressed core, governed by improvisation and local leverage.

The state endured, but it endured within a narrower frame—bound by its own constraints, and dependent on the inertia of survival.

Final Thoughts: When Maps Shatter Dreams

Geography once offered Mexico a geopolitical jumping off point: two oceans, mineral mountains, fertile valleys, strategic frontiers. History, through war and folly, shattered that offer, and sealed a different fate.

The Mexican-American War forced a structural reorientation. With the loss of Texas, New Mexico, and Alta California, Mexico ceded the terrain through which it once imagined scale, depth, and projection. Those territories offered surplus, mobility, and leverage. Their removal narrowed the scope of national purpose, and resources it could’ve used to rival the fledgling United States in the 1840s and 1850s. Mexico, stripped of these assets, entered the 20th century with a weakened industrial base.

Today, Mexico remains affected to the consequences of that loss. Its economy orbits the American core. Profitable warehouses and factories sit on US borders, while migrants are pulled northwards to work in territories that it lost.

Its politics still wrestle with the legacy of lost ambition, the memory of territories once mapped but never truly held.

Thanks for reading.

Before then, if you have any questions or comments, feel free to comment and follow me:

Bluesky: pplsartofwar.bsky.social

Like that previous vast territory on the opposite side of the continent. New France had the makings of a powerful empire, but lacked the population to control it against an expansionary Thirteen Colonies.

This is so thorough and well written. Thanks for sharing! Looking forward to reading more of your work.