China’s history with Tibet is a complicated one, but ultimately an existential geopolitical one. The language surrounding Tibet is often framed in moral or cultural terms, but this obscures the harder truth:

States do not hold geographical regions out of sentiment. They hold it because geography demands it for their survival.

The Plateau stands as the intersection of civilizational memory and strategic necessity. Its elevation isolates it, but also empowers the nations whose borders draw red and often disputed lines across it.

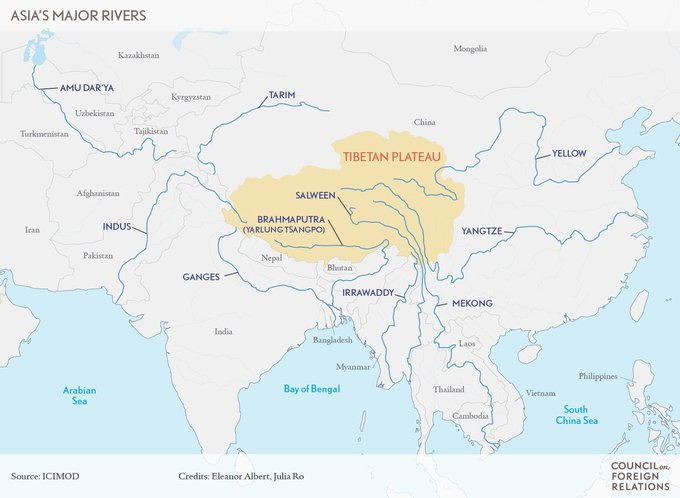

From its heights, China touches the Himalayas, surveys the Central Asian steppe, and oversees the headwaters of rivers that nourish the Indo-Pacific basin. And few regions in Asia carry such persistent relevance across dynasties, ideologies, and eras.

From empire to republic to party-state, the logic holds firm: the Tibetan Plateau secures China’s west and shields the heartland.

The Southern Great Wall

The Tibetan Plateau acts as a natural barrier - a Southern Great Wall of China. Its towering heights and rugged terrain make invasions from the south extremely difficult.

Historically, this has protected China’s heartland from incursions via the Himalayas. The plateau served as a defensive moat during times when China’s lowland core—particularly the Sichuan Basin and the central plains—was vulnerable to instability. Chinese dynasties from the Yuan Dynasty onward sought to vassalize or control it.

In modern times, it also allows China to hold its southern border, securing Xinjiang and the western regions. Control over the plateau creates a secure dominance in the Himalayan frontier, preventing rival powers from establishing a foothold.

Power is defined by a nation’s capacity to impose limits on the options of others while preserving a wide array of choices for itself.

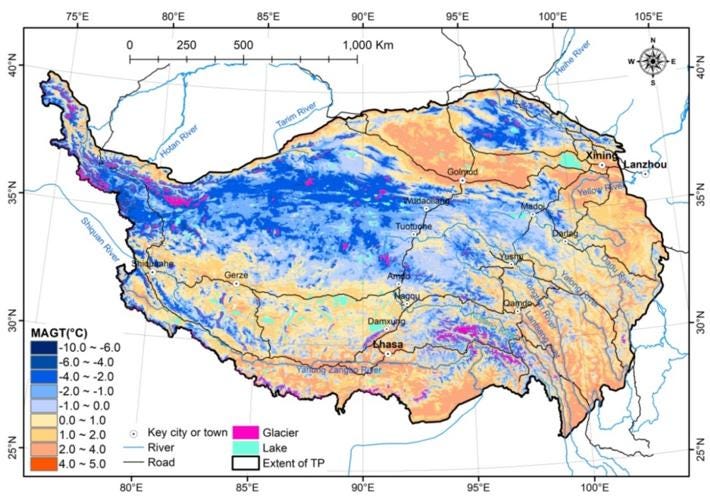

Tibetan Plateau offers exactly this form of strategic leverage. Its extreme altitude, unforgiving terrain, and scarce oxygen create a natural wall so imposing that it renders conventional military incursions from the south into China extraordinarily difficult. It is not terrain to cross, but a high altitude gauntlet. Where supply lines and men fray before the first shot is fired. It is, in essence, a natural deterrent.

The length of the plateau also gives strategic depth. Its a vast expanse of high terrain stretching over 2,500 kilometers from west to east. This breadth creates layers of defense and that delay and exhaust any force attempting to cross it. Even if an adversary were to breach the outer rim of the Himalayas, they would still face a punishing journey before ever reaching China's interior. In strategic terms, the Tibetan Plateau transforms the southern border from a line into a zone—a buffer that buys time, absorbs force, and multiplies the costs of an incursion.

The plateau’s sheer scale also allows for mobility within depth. With huge defensive and offensive implications. Roads, airfields, and outposts across the plateau enable China to redeploy forces east to west as needed, acting as an internal frontier highway that supports flexibility and rapid reaction across multiple border regions.

This is especially important in a world where flash conflicts and border standoffs can escalate quickly. The plateau gives the PLA not only the stereotypical high ground, but also critical ability to maneuver across that high ground. Take that away and you point a long sharp spear at the Chinese heartland.

No foreign army has successfully marched into China from the south through the Himalayas in modern times. This is not by coincidence, but by the brutal geometry, geography, and climate of the plateau.

The Tibetan Plateau is impermeable natural fortress that secures its southwestern flank.

As Kissinger observed in On China, Beijing has always prioritized strategic depth whether through control of Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, or the Northeast (Manchuria). Tibet provides exactly that. The Himalayas act as a near-insurmountable barrier, forcing any potential adversary into a position of perpetual disadvantage. Or great advantage if they can take it.

And there’s a geographical feature control of it protects.

The Hexi Corridor

Control of the Tibetan Plateau means a strong position to threaten a major East to West corridor in China: the Hexi Corridor.

For over two millennia, the Hexi Corridor has linked China to the western world, its narrow spine wedged between the high white summits of Qilian Mountains and the deserts of the Gobi.

The corridor's historical significance cannot be overstated.

During the Han Dynasty's westward expansion, it became the vital artery of the Silk Road, with its string of oasis towns - Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan, and Dunhuang - serving as crucial waystations for caravans bearing silk, spices, and ideas between China and the distant Roman Empire.

But its vulnerability of this route has always come from the fact that it is hemmed in on both sides—by the Mongolian steppe from the north, and by the Tibetan highlands from the south. Control of both flanks has been the sine qua non of securing this artery.

The Tibetan Plateau gives the southern flank its gravity. From its heights, any power can observe movements along the corridor, interdict supply lines, or project force across the northern frontier with relative ease.

The Tang Dynasty learned this the hard way in 763 AD, when Tibetan cavalry surged down from the plateau, pierced the Hexi defenses, and seized Chang’an—the glittering imperial capital. It was a devastating reminder that Tibet is a platform from which campaigns can be launched deep into the Chinese heartland.

Over the centuries, this memory hardened into doctrine. Dynasties from Han to Qing pursued a dual containment strategy: secure the corridor itself, and neutralize or co-opt the powers who controlled the heights above it. Tibet was too exposed to ignore, too elevated to leave unconsolidated. Whether through vassalage, alliance, or outright conquest, Chinese statecraft has consistently recognized that the Hexi Corridor cannot be held in isolation—its safety depends on the status of the Tibetan Plateau above it.

Today, the logic remains unchanged. The same elevation that gave Tibetan cavalry a launchpad in the 9th century against the Tang Dynasty now enables airpower, surveillance, and strategic basing.

Chinese high-altitude airfields in Tibet can project force across the Qilian Mountains and into the corridor below, offering defensive depth and aerial dominance. Tunnel systems carved into the Tibetan and Qilian highlands provide secure storage, transportation, and missile deployment zone. Its a historical echo of the same fear and existential need that once built watchtowers and forts along the Silk Road.

The Hexi Corridor remains a vital artery for China’s energy security and westward integration. Pipelines, highways, and the Lanzhou-Xinjiang railway snake through it, linking the industrialized east to Central Asia’s resource fields. But the infrastructure on the ground is only as secure as the heights that loom silently over it.

Strategic geography teaches one immutable truth: no power can secure the Chinese west without controlling the plateau that shadows it. The Hexi Corridor may be the road, but Tibet is the ridgeline that determines whether that road remains open—or becomes a vulnerability. The Plateau is a defensive shield or a contested frontier. It is the spatial high ground of Chinese power projection, a timeless glue that binds Xinjiang and the western regions to the Chinese heartland in the East.

Control Over Water

Control over water systems is one of the most quietly consequential forms of geopolitical influence. The Tibetan Plateau is no different - and who controls the headwaters of rivers give them significant leverage. There’s a reason why.

Rivers are infrastructure, lifelines for agriculture, energy, and human settlement. The country that controls the headwaters of a major river system gains a degree of leverage that is rarely acknowledged but deeply significant.

Historically, empires and modern states alike have sought to control entire river systems as a means of ensuring internal stability and economic integration. The United States has long leveraged its control of the Mississippi River system to unify its industrial and agricultural core. Russia has done the same with the Volga. Brazil manages the Amazon system for development and defense. And China’s control of the Yangtze and Yellow River basins has historically underpinned its food security and population centers.

What makes the Tibetan Plateau distinct is the international scope of its hydrological impact. It is rare for a single region to feed so many rivers flowing into so many countries. In this context, hydrological infrastructure—dams, canals, data stations—becomes part of a broader regional balance, not just a domestic concern.

The Tibetan Plateau is the largest freshwater reserve outside the polar ice caps, feeding ten of Asia’s mightiest rivers, including the Yangtze, Mekong, Brahmaputra, Indus, and Ganges. Its often called the “Third Pole” for this reason - it contains a vast amount of water.

The geopolitical implications of controlling these headwaters are immense, giving a China influence and diplomatic leverage in regional politics.

For China, this serves as leverage in certain ways:

Diplomatic Influence: Control over upstream flow gives China a quiet but powerful voice in downstream water politics. Agreements or disagreements over dam construction, seasonal releases, and flood control can affect agricultural yields, hydroelectric production, and even internal political stability in countries like India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Myanmar.

Hydropower and Energy Security: High-altitude dam systems like those on the Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) and Lancang (Mekong) provide renewable energy to inland provinces, while also giving China the ability to regulate water flow into Southeast Asia. This dual role as energy provider and upstream regulator makes infrastructure decisions carry regional consequences.

Strategic Buffering: In the event of geopolitical tension or conflict, the control of river sources offers a non-military form of coercion or deterrence. Reductions in flow, whether caused by drought, infrastructure operation, or upstream storage, can create downstream disruptions without requiring overt confrontation.

Climate Adaptation Leadership: As Himalayan glaciers retreat and rainfall patterns shift, data from Tibetan hydrology stations becomes essential. Whoever controls the monitoring systems controls early warning, resource forecasting, and disaster management coordination. This scientific edge can be translated into regional leadership.

In short, the rivers that begin in Tibet aren’t isolated from geopolitical implications. Control over their water and the broad consequences flow outward, tying the fate of distant deltas and floodplains to decisions made on the Plateau. Power over water is not supply—it is about timing, predictability, and control. Civilizations have fought and negotiated over river systems for millennia for this reason.

But the broader truth remains: as water stress deepens across the continent, the decisions made atop the Plateau will echo far beyond its borders. The rivers that descend from Tibet carry not only water—but power, perception, and the terms of interdependence.

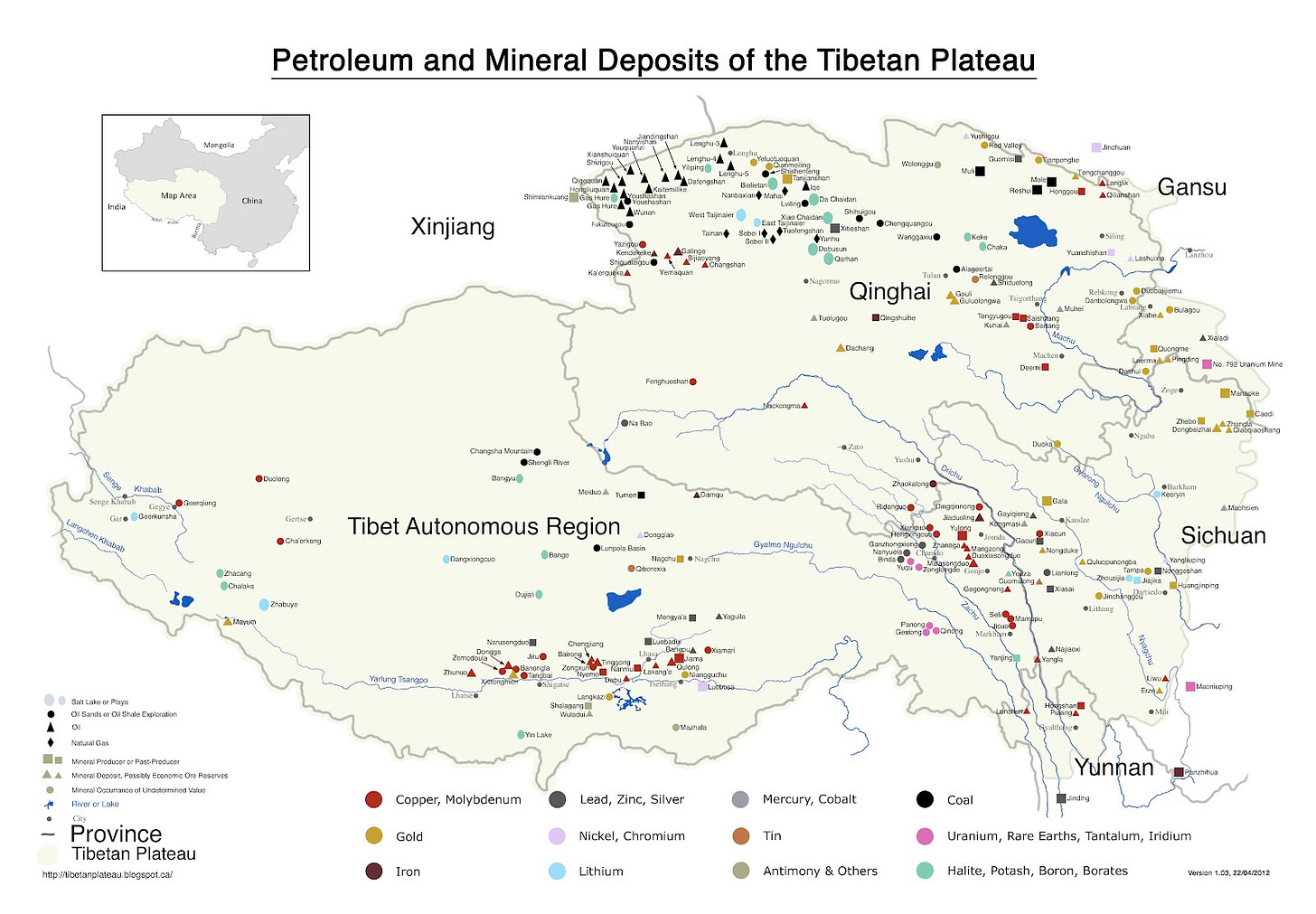

The Silent Treasury: Tibet’s Mineral Wealth

The Tibetan Plateau is more than a wall and a watershed. It is also a vault.

Beneath its glacial crust lies a treasury of strategic minerals, copper, lithium, rare earths. With each one a cornerstone of modern mineral power. In an era shaped by electrification, artificial intelligence, and precision warfare, these elements form the raw circuitry of geopolitical strength.

Estimates place Tibet’s copper reserves at over 30 million tons. The Qulong and Yulong mines sit among the largest in Asia. A lode like this is not only industrial convenience, but a strategic foundation for powering industries. Copper carries power across continents. It fortifies grids, fuels industry, and wires the nervous system of the state. A country without copper builds nothing. A country that controls it dictates the tempo of construction and the pace of recovery in crisis.

Lithium flows from the salt lakes of Zabuye and Dangxiongcuo, where over two million tons of proven reserves anchor China’s position in the global battery race. In Ngari and Nagqu, entire basins serve as extraction zones for the substance that powers mobility, autonomy, and storage—from hypersonic weapons to civilian EV fleets. This is energy security rendered in crystal form.

Rare earths complete the triad. From jet propulsion to missile guidance, they animate the future of warfare. Tibet adds depth to China’s rare earth supply not only through quantity, but through their strategic geography. In strategic terms, this is not only possession. It is insulation from disruptions in an event of a trade or kinetic war. These deposits exist within the borders of the state, not within the reach of foreign supply chains.

Geography becomes custody. Custody becomes leverage.

The extraction effort is no longer exploratory. Qulong alone is projected to yield 165,000 tons of copper per year. Lithium production now supports entire supply corridors reaching into Sichuan and Jiangsu. The Qinghai-Tibet railway, once a political symbol, now moves minerals east at scale. What once took months now arrives in days. And what once served pilgrims now serves production.

This is industrial strategy with imperial memory.

Dynasties once built forts to guard mountain passes. The modern state builds infrastructure to extract and transport what lies beneath. Roads, rails, pipelines, and power grids trace the map of the future.

Every ton removed from the Plateau alters the strategic balance by an invisible degree, which is missed in weapons and political debates. But underpins the sustainability of China’s ambitions.

Final Thoughts

Tibet is elevation. Tibet is water. Tibet is time. But it is an intersection of strategic interests that go beyond just ideological debates, and on sustaining China’s development into the 21st Century.

Beneath its vast skies lies a simple truth: geography dictates necessity. The Plateau’s glaciers water China’s farms and cities. Its heights dominate the Himalayan frontier. Its mineral veins – copper, lithium, rare earths – underpin industrial and technological dominance. These are not political choices, but strategic imperatives written in terrain.

The question is not whether Tibet matters, but how its strategic weight will be managed in an age of competition. And beneath the azure Tibetan sky lies the material foundation for any Chinese state that intends to last.

In this context, narratives around Tibet are often shaped by these broader anxieties. Questions of autonomy, access, and control intersect with environmental concerns and national development goals. The goal for all parties is to make guarantees that the Plateau remains not a point of tension, but a shared foundation for stability in an increasingly interdependent region.

Thanks for reading.

Before then, if you have any questions or comments, feel free to comment and follow me:

Bluesky: pplsartofwar.bsky.social

Great post... really informative.

Several of these rivers are expected to see reduced flow within the next few decades as the ice pack feeding them continues to shrink. Control over the Tibetan Plateau will become even more strategically important. Countries like Myanmar, Thailand, India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan may face increasing pressure to either cooperate with or push back against China's control of these critical water sources.

Reading this made me appreciate how fortunate we are to have the Mississippi River system. Our vast network of navigable rivers flows through some of the most fertile farmland on Earth. A huge strategic and economic advantage we shouldn’t take for granted.

Thanks. Learned a lot.