The Timeline #1: Why won't Iran close the Strait of Hormuz?

And the deeper reasons behind it - that get lost in the noise

During the recent Iran–Israel conflict, Iran’s parliament passed a resolution to close the Strait of Hormuz - one of the world’s most important energy corridors. The move came just after a ceasefire was brokered between Iran and the U.S., following strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities.

But not without one final gesture: Iran’s parliament passed a formal resolution to close the Strait of Hormuz, contingent on approval by its Supreme National Security Council. Oil markets twitched. Headlines screamed. Yet tankers kept moving.

That gap, between the threat and the outcome, is a consistent facet of story.

So this week, we’re unpacking why Iran rarely closes the Strait, even when it signals it might:

What is the Strait of Hormuz, and why does it matter?

It’s the narrow maritime chokepoint through which roughly 20% of the world’s oil flows. Whoever controls it, controls a global pressure valve. But controlling doesn’t mean closing.

Disruption is easy. Control is expensive.

Iran has the means to interfere, mines, missiles, fast boats, but not to maintain sustained closure. Its doctrine favors sharp jolts over extended campaigns. Keeping the strait shut for more than a few days would stretch its resources and invite dangerous unpredictability.

Closure would affect Iran’s silent partnerships.

Russia, China, India tolerate tension, not chaos. But so do Gulf states like Qatar, Oman, and the UAE, many of which serve as Iran’s unofficial diplomatic backchannels. Closing the strait would collapse that quiet architecture.

Iranian Political Theater. Since the Iran–Iraq War, Tehran has repeatedly threatened to close Hormuz at least 4 times. Political theater is a feature not a bug, when it comes to Iranian threats to close the Strait of Hormuz.

Economic threats are a diplomatic bargaining chip. Threats that are made can be more effective than imposing consequences.

Let’s break it down a bit.

The bottom of this article could be cut off in some email clients. Read the full article, unbroken here.

1. What is the Strait of Hormuz, and why does it matter?

The Strait of Hormuz is the most important energy chokepoint in the world. It connects the Persian Gulf to the open ocean. By extension it links the economies of the Gulf to Asia, Europe, and beyond. There is no alternate route.

That’s what makes it a critical vital artery for the Gulf States. The Strait of Hormuz is where global oil supply, geography, and military tension all collide.

Geography: Narrow, exposed, and unforgiving

Most people think of it as a wide stretch of water. It isn’t.

Its narrow. At its narrowest point, the Strait is about 33 kilometers across. But only 6 kilometers are deep enough for supertankers. These are split into two traffic lanes: one inbound, one outbound, with a small separation buffer. Movement is tight, timed, and continuous.

Two nations touch the strait. To the north is Iran. To the south is Oman’s Musandam Peninsula. Both coasts are elevated and rocky, with natural sightlines across the lanes. Surveillance equipment, anti-ship systems, and radar installations can operate from hardened ground within range of most of the corridor.

There is no real bypass. To exit the Persian Gulf, every large vessel, commercial or military, must go through Hormuz. There are no secondary straits, no parallel channels, no alternate deep-water exits. If you want to leave the Gulf, you pass through this funnel.

Tightly controlled. At the eastern mouth of the Strait sit three small islands: Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, and Lesser Tunb. Iran has fortified them since the 1970s. From their position, they offer direct line-of-sight over the shipping lanes and form a fixed surveillance triangle.

So this is not just a logistics route. It is a compression point for naval, commercial, and diplomatic movement. Small actions taken here can ripple outward fairly easily. And it has great outsized importance.

Economic Importance.

The Strait of Hormuz is the most important energy chokepoint in the world. Around 17 to 18 million barrels of oil pass through it daily. Roughly 20 percent of global consumption. These are not marginal flows. They underpin the functioning of multiple economies.

Daily traffic includes oil and gas exports from:

Saudi Arabia

Iraq

Kuwait

The United Arab Emirates

Qatar, whose liquefied natural gas exports are among the most globally traded

Smaller Gulf producers with no alternative maritime exit

These flows are critical to East Asia in particular. China, Japan, India, and South Korea all rely on uninterrupted deliveries from the Gulf. Europe draws less but still depends on Hormuz for part of its long-range energy mix.

There are pipeline alternatives, but they don’t scale. Saudi Arabia’s East–West pipeline to the Red Sea moves up to five million barrels per day—less than one-third of Hormuz capacity. The UAE’s Habshan–Fujairah line carries about 1.5 million barrels. Iraq’s overland options through Syria or Turkey remain politically fragile and logistically constrained.

These routes also come with their own risks. Pipelines are static, vulnerable to sabotage, and harder to reroute. They rely on domestic stability and regional coordination. None of them offer the flexibility, volume, or resilience of deepwater shipping.

Which is why the Strait must stay open. Disruptions, even minor ones, have immediate ripple effects. Refiners schedule cargoes weeks in advance. Tankers are booked based on route integrity. And pricing models assume uninterrupted flow. So a disruption has huge consequences.

Military Importance

The Strait of Hormuz is a natural military chokepoint . Its narrow, rocky geography compresses movement, limits evasion, and magnifies risk.

Every aspect of the terrain favors the defender or disruptor:

Large tankers move slowly and on fixed paths

Submarines have almost no room to maneuver

The channel is shallow, flanked by cliffs, and fully exposed to land-based weapons

This is why Hormuz features in every serious military contingency plan involving the Gulf. Naval exercises, wargames, and force deployments, from the United States, United Kingdom, France, and China - routinely simulate conflict scenarios here. Not because they want to fight in the strait, but because if conflict starts anywhere in the region, it likely passes through here.

Control of the strait means more than holding water. It means:

Real-time visibility on all tanker and naval movements

Control over global narrative and market expectations

Psychological pressure that extends beyond the region

Military presence in the area is constant. Fleets operate just outside the strait. Surveillance aircraft rotate through allied bases. Port access in Oman, Bahrain, and Djibouti supports quick naval response. Any serious power with Gulf interests either maintains access - or builds contingency plans around those who do.

The Strait of Hormuz is not a hypothetical flashpoint. It is preloaded with tension where even a misinterpreted maneuver could shift global balances in a matter of days.

For the most part, the Strait of Hormuz (along with other major choke points like Suez, Horn of Africa, Malacca Strait) is a major strategic advantage to control. And Iran is positioned ideally to slip a noose around the Gulf State’s neck.

But why hasn’t it been able to?

2. Disruption is easy. Closing it off is expensive.

Closing off a naval choke point like the Strait of Hormuz is easy to start. Sustaining it is something else entirely. Geopolitical leverage relies not on the ability to act - but on the ability to hold it.

It does little for a carpenter to have a hammer to build a house, and have a shortage of labor and nails. Power in the Gulf operates on the same principle, not just for Iran, but for the other Gulf States.

A chokepoint is not controlled by the one who can close it. It is controlled by the one who can afford to keep it closed.

The tools for disruption are known- and proven.

Iran has already demonstrated a credible capacity to interdict and disrupt maritime traffic in the Strait of Hormuz. Its toolkit is built not for sustained control, but for denial in time and space—sufficient to trigger systemic response without requiring maritime superiority.

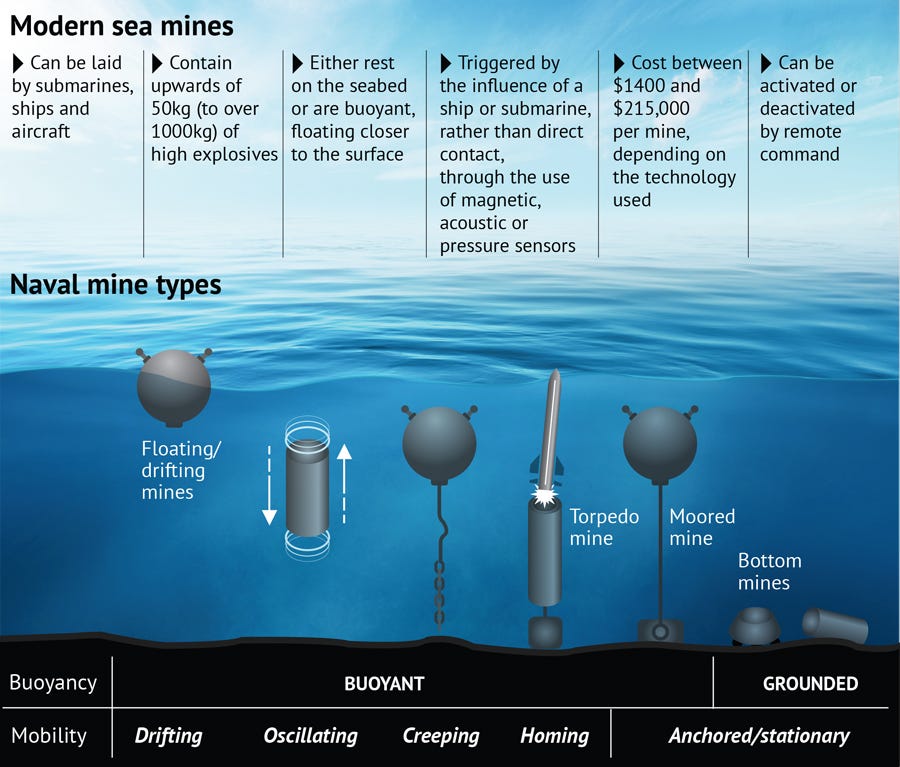

Naval mines are Iran’s most asymmetric asset. They can be deployed covertly by small craft or mini-submarines in minutes, yet clearing even a handful can take days of specialized mine countermeasure operations. Especially in narrow lanes like in the Strait where civilian traffic cannot be rerouted. Iran was planning to use this if the recent conflict escalated.

Swarming fast-attack craft, often operating in units of 10 to 30, use high speed and coordinated harassment to approach tankers or warships at close range . They’re difficult to track, harder to deter, and nearly impossible to eliminate without engaging in force escalation, significant naval presence, or convoys.

Mobile anti-ship missile units, including variants of the Noor (C-802) and Qader, are dispersed along Iran’s southern coastline. Launched from hardened or concealed positions, these missiles can range most of the strait and are tied into redundant radar and electro-optical tracking systems. They are designed to fire-and-displace—survivable, mobile, and layered.

Armed drones. Particularly the Shahed-series, offer Iran a scalable harassment tool. Their use in Ukraine has demonstrated how saturation attacks can overwhelm defenses and complicate targeting priorities. In the Gulf, they could be used to shadow convoys, disrupt formations, or strike isolated tankers - low cost, high visibility.

These platforms are not meant to win a naval engagement. They are meant to raise the operational risk environment. Their effectiveness lies not in overwhelming force but in cost imposition: force every ship to second-guess its route, every insurer to adjust its premiums, every command structure to go into contingency posture.

But disruption is not closure. These tools can make passage dangerous. They cannot make it impossible. And any sustained attempt to close the strait would require multi-domain denial against a far more capable adversary - with Iran absorbing the escalation consequences.

Control is far harder.

What control would require?

The illusion of control lies in the first disruption. The reality of power lies in a nation’s ability to maintain it after the system adjusts.

Actually sealing the strait means something far more difficult:

Sustaining constant threat against a high volume of moving targets, day and night. Tankers don’t pause for conflict—they keep coming, which means the threat must be continuous, not symbolic.

Defending forward positions under persistent surveillance and the certainty of naval retaliation. Any launch platform would be quickly located, targeted, and struck—requiring mobility, redundancy, and hardened infrastructure.

Operating under real-time surveillance from satellites, drones, and manned aircraft. While using up resources to deter and counter that. The Russian experience in Ukraine has shown how quickly the tempo of combat operations and battle surveillance has become.

Surviving counterfire from long-range missiles, submarines, and electronic warfare systems. Retaliatory strikes would come not just from surface ships but from the full spectrum of Western and Gulf capabilities.

This is not a one-day blockade. It is a 24/7 combat posture with cyber, military, and logistics that must be sustained in one of the most closely monitored maritime spaces on Earth.

Iran (or any actor attempting closure) would have to manage all of this while cutting off its own revenue and risking escalation with every hour the strait remained shut.

Logistics is a major hang-up.

Closing Hormuz for more than 48 hours means managing:

Sustainment. Iran would need significant stockpiles of its most effective systems: anti-ship missiles, naval mines, drone platforms, and radar assets. These are expensive, often imported in components, and difficult to replace under sanctions. Once fired, they are gone.

Command and control depends on logistics. Maintaining operational coordination requires physical movement of fuel, ammunition, and spare parts across dispersed units. Iran lacks the protected transport routes, hardened depots, and redundancy to keep those links functioning under sustained pressure.

Fuel and rearmament for small craft. Iran’s fast-attack boats are short-range assets. Sustained operations require shoreline refueling and rearming points that are both exposed and vulnerable to interdiction. Interrupting those flows collapses the tactic.

Dual-use infrastructure under stress. Iran relies on civilian ports, roads, and energy corridors to move both commercial goods and war materiel. Once those are hit, it cannot reroute. Every strike on its logistical grid undermines both the military campaign and the national economy.

Sustained closure is an endurance test. One few states can pass. Certainly not without suffering more damage than they inflict. Usually only a very powerful nation with full spectrum power projection and logistics can sustain this - such as the United States, China, etc.

Any state can scatter mines or launch a salvo. But the measure of power lies in what remains functional after the enemy has answered. A blockade must survive contact not just with adversaries, but with time itself.

3. Closure would affects Iran’s silent partnerships.

Threatening to close the Strait of Hormuz wins headlines. Actually doing it would collapse Iran’s external balancing strategy overnight. It still has a two way relationships with other powers - were both would mutually be affected.

For years, Iran has walked a tightrope: confronting the U.S. and its allies while quietly building relationships with countries that don’t share Washington’s worldview. That balancing act depends on ambiguity. A full blockade would erase it.

China, Russia, India are partners, not pure patrons

These powers have no interest in seeing Hormuz closed. They may tolerate confrontation. Patrons absorb risk. Partners do not. China, India, and Russia may sympathize with Iran’s position, but mortgage their energy security is sticky for them.

After all, they have interests to preventing a Hormuz blockade:

China relies on Hormuz for over 40% of its crude oil imports. Not to mention exports of consumer goods to the Gulf nations would be cut. There’s also heavy investments in Gulf infrastructure through Belt and Road channels. A shutdown would force Beijing to choose between energy security and its strategic relationship with Iran. That’s not a choice Iran wants to force lightly. It wants it to act as mediator aligned with it.

India maintains energy ties and infrastructure projects like Chabahar, but its strategic calculus is cautious. New Delhi walks a fine line between Iran, Gulf Arab states, and Washington. Any Iranian action that closes Hormuz would force India into a position it has long avoided- choosing sides in a regional confrontation.

Russia coordinates with Iran strategically, in Syria, in arms sales, and in diplomatic forums, but it is not a guarantor of Iranian policy - even with an existing strategic pact. The strategic pact also includes several clauses aimed at boosting economic partnership, so it could stand to benefit. A closure might raise oil prices temporarily, but it would also invite greater Western and Asian alignment around energy diversification, including petroleum competition that undercuts Russia’s market position.

Each of these states tolerates Iranian tension as long as it remains calibrated. What they will not support is a unilateral act - like closing the Strait of Hormuz -that threatens global energy flows and forces them into costly diplomatic realignments.

Iran may have strategic partners, who are willing to mediate diplomatically on its behalf. But it does not have a patron willing to absorb the price of higher escalation.

It is a mistake to assume alignment means commitment. External partners engage with Iran to balance their interests, not to fulfill its ambitions. The minute Hormuz becomes a global liability, those same partners begin managing the fallout, not defending the cause.

Gulf backchannels would be strained.

Less visible, but equally important, are Iran’s relationships with its immediate neighbors: Qatar, Oman, and to a quieter extent, the UAE. These states are not friends Iran, but they are essential diplomatic backdoors for Iran:

Oman has acted as a go-between in U.S.–Iran negotiations for over a decade. Its neutrality depends on regional stability.

Qatar hosts U.S. forces but maintains economic and political dialogue with Iran, particularly over shared gas fields. That dialogue collapses under sustained escalation.

The UAE, despite tensions over the islands, has restored limited trade and diplomatic relations. Closure would reverse that trend immediately.

So closing the Strait, Iran would not just provoke its enemies. It would alienate the few actors still willing to speak on behalf it diplomatically, economically, and politically. Closing those channels prevents any de-escalation and any leverage they have over Western powers.

The Gulf backchannels are not friendships. They are pressure valves. Oman, Qatar, and the UAE offer Iran a space to negotiate without losing face. But that space disappears when diplomacy is replaced with escalation.

The audience that matters isn’t the adversary - it’s the bystander

A state does not secure its interests through force alone. It secures them through the choices it gives others. The real danger of closing Hormuz isn’t U.S. retaliation. It’s the removal of choice from neutral or ambivalent powers that had been willing to stay on the sidelines. Or even align in Iran’s favor to further their own interests.

India cannot hedge if its tankers are stopped, and industries affected. China cannot hedge if its factories risk fuel rationing or manufactured goods cannot reach prime markets in the gulf. Even Russia cannot hedge if its clients demand stability. When options collapse, actors realign against those who cause it. Coalitions form not through ideology, but through shared necessity.

A full closure of Hormuz closure ends it in the eyes of neutral or involved states. Once hedging becomes impossible, powers stop managing Iran—they begin containing it

4. Iran threatening closure isn’t new. It’s a political theater.

States repeat actions not because they lack imagination, but because certain patterns prove strategically reliable. Since the 1980s, Iran has returned to the same formula: threaten to close the Strait of Hormuz, raise the cost of confrontation, then step back before consequences become irreversible.

The origins: coercion without collapse

The model emerged during the final years of the Iran–Iraq War, when the Gulf transformed from a commercial corridor into a theater of attrition. Iraq struck Iranian oil infrastructure; Iran responded by targeting oil tankers. What followed, known as the Tanker War, was less an attempt to destroy energy flows than to degrade the assumption of safety. From 1984 to 1988, over 400 ships were hit.

But the strait remained open. The goal was never its closure, even for a radical and determined leader like Ayatollah Khomeni. The goal was to compel global powers—especially the United States—to internalize Iran’s relevance.

It worked. By 1987, the U.S. had begun reflagging Kuwaiti tankers and escorting them under naval protection. What had been Iran’s war with Iraq became a regional confrontation in which Washington had to play a direct role—if only to keep oil flowing and alliances intact.

This has been the framework going into the 21st century. But modified for a more globalized conditions.

The doctrine: escalate, extract, retreat

What began as battlefield improvisation during the Iran–Iraq War became something more permanent. Over time, Iran turned a tactical contingency into a repeatable doctrine.

When under pressure, Tehran doesn’t escalate to win. It escalates to reframe:

2008: In response to terrorism designations against the IRGC, Iran declared it could shut Hormuz “in minutes.” Prices surged. Nothing closed.

2011: When EU sanctions threatened oil exports, Iranian officials warned of retaliation at sea. The U.S. Navy increased its presence. The threat receded.

2019: After the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal, Iran escalated in form—mining tankers, seizing a British ship—but not in substance. Traffic continued.

2025: Following airstrikes on nuclear infrastructure, Iran’s parliament approved a resolution to close Hormuz. But execution was deferred. As before, ships moved, headlines churned, and the ambiguity remained intact.

Each cycle follows the same structure. Create pressure. Force a reaction. Step back. Iran tests boundaries without crossing them. It wants to be seen as dangerous - just not reckless.

Hormuz is the perfect instrument for this kind of signaling. It links oil markets to security debates. It draws in powers that would otherwise keep their distance. And as long as the strait remains open—but unstable—Iran stays relevant. That’s the point.

Why political theater over closure?

Calibrated tension is the concept to know here. The strategic purpose behind it is to signal capability without committing to escalation. Each diplomatic action has the point of raising stakes and suggesting costs. Its to suggest what could happen, and to force adversaries to prepare for outcomes that never arrive.

Its a very similar strategy to North Korea. Each escalation is meant to redraw the boundaries of normalcy. Its to condition the international system to accept a new baseline without crossing the threshold that invites war. The tactic works because the line between coercion and instability remains blurred, and because adversaries often prefer managing risk to testing it.

Iran threatens without acting not only because it is bluffing, but because it gains more from the performance than from the act. The message is not, “We will close Hormuz.” The message is, “We can, and we might, if pushed too far.”

Personally, I think it’s a legitimate tactic for small states. When facing adversaries with superior firepower, global reach, and economic leverage, the threat of disruption may be the only card available. Deterrence through ambiguity allows weaker powers to shape behavior far beyond their material strength. It doesn’t solve their structural vulnerabilities. But it does buy time, space, and leverage.

5. Economic threats are a bargaining chip.

For Iran, the Strait of Hormuz is more than a transit corridor. It is a pressure valve. Each time Iran signals a potential disruption without following through, it leverages the structure of global markets to increase its influence. The threat alone is often more powerful than the act.

Ambiguity creates strategic leverage

Iran dies understand that in the global energy system, the mere suggestion of risk often creates greater impact than escalation itself. By hinting at closure, it moves prices, forces recalculations, and draws diplomatic attention. That attention becomes leverage and follows a path:

Energy markets respond immediately. A legislative resolution, a military exercise near shipping lanes, or a targeted statement from Iranian leadership is often enough to move Brent and WTI futures within hours.

Insurance premiums rise quickly. Tankers entering the Gulf region face elevated costs even in the absence of direct conflict. Perceived instability is priced in faster than verified threat.

Port authorities and shipping firms adjust operations. Cargos are rerouted, hedged, or delayed not because closure is imminent, but because the uncertainty is real.

Third-party governments take notice. Countries like China, India, and the Gulf states have strong interests in maintaining the flow of energy. A credible Iranian threat to Hormuz forces them into quiet mediation, not because they endorse the move, but because they wish to avoid its consequences.

Diplomats begin working behind the scenes. Statements are softened, channels reopened, and broader negotiations often begin around the margins of the energy conversation.

By keeping Hormuz open but unstable, Iran gains a relative advantage and initiative in diplomatic plays. So that a Hormuz closure remains at the center of every major energy contingency plan. That centrality is strategic capital.

Closing the Strait would eliminate that economic leverage.

If Iran were to formally close Hormuz, it would immediately undermine its own economic and strategic position. The consequences would be rapid, and many would be self-inflicted.

Iran’s own oil and gas exports move through the Strait. So do its industrial imports, medical supplies, and refined products. A closure would halt critical revenue and strain the domestic economy.

Major partners would be forced to respond. Countries that tolerate Iran’s signaling might pivot away if energy flows were cut off. The ambiguity that keeps them engaged would be replaced by the clarity of crisis. It takes away diplomatic initiative and forces unfavorable alignments.

Market mechanisms would recalibrate. Strategic reserves would be deployed. Alternative routes would open. Producers in the Gulf would raise output. Over time, Iran would lose control of the very panic it triggered - and strategic ambiguity is no longer an asset at that point.

The logic is simple. Iran gains influence not from action, but from the ability to imply action. The Strait of Hormuz is most useful when it is open, vulnerable, and uncertain. That uncertainty gives Iran space to bargain, project relevance, and extract attention from powers that would otherwise look elsewhere.

So its useful for three diplomatic reasons:

Threats keep the conversation going.

As I’ve said before, a very effective way to keep a political conversation alive is to threaten. Not necessarily to escalate, but to suggest that you could. Iran knows this well. The moment it signals something like closing Hormuz, it forces others to engage, whether they want to or not. Countries start calling, envoys start flying in, and backchannel talks open up. It doesn't matter whether anyone believes Iran will follow through. What matters is that the conversation doesn’t stop.Market reactions keep the pressure high.

From a strategist’s point of view, market panic isn’t just noise. It’s pressure. When oil benchmarks spike, Iran knows the pain doesn’t land evenly. It lands on importers, refiners, shipping insurers, and domestic fuel buyers. That creates friction between industries and governments. Tehran doesn’t need to convince a foreign leader to change course. It just needs enough volatility that influential sectors within that state start lobbying for de-escalation. The pressure gets outsourced.Diplomacy stays in motion.

Static diplomacy benefits the stronger party. Movement creates openings. As long as Iran keeps the Strait uncertain but technically open, it forces others to stay flexible. The ambiguity creates space for maneuver. Iran may not be able to dictate outcomes, but it can influence timing, slow down initiatives, or reopen channels that had gone quiet. That’s not weakness. It’s tempo control. And for a state with limited resources, controlling or injecting tempo is sometimes the only form of power that matters.

It is a chokepoint of leverage. Iran keeps it open and makes threats, because strategically it is more powerful and relevant to the region that way. Better to make your opponents and neutral parties feel the consequences, than to be regionally irrelevant.

Takeaways

Its only been a month since the last conflict. But Iran reused its old playbook with some slight modifications. This has been Iran’s consistent posture since the 1980s - to buy time for political maneuvering, while threatening the strait.

In any future conflict, I expect them to do the same. A massive overwhelming force initially to signal. while maneuvering behind the scenes to their advantage. There’s nothing wrong with that. There’s nothing wrong with that. Iran cannot sustain a massive blockade of the strait. Its survival strategy depends on shock without follow-through, and leverage without overextension. It plays for time, not for victory.

I do not think this policy can last forever. Threatening the Strait of Hormuz to extract concessions is a age old tactic. But lacks teeth as long as there is no political will to enforce it - or a larger patron willing to fund it. Brinksmanship takes more than nerve. It requires fuel, replacement parts, hard currency, and diplomatic cover. It needs someone willing to pay the full bill for escalation, or a regime willing to absorb real risk. Iran has neither yet

But there are signs to watch if this policy shifts. The big one here is the involvement of a larger nuclear armed great power like Russia or China. Not just a trade or weapons agreement, but a formal defensive pact or defacto one that defines how they intervene. There’s a mindset now that trade agreements = defensive obligations. Which they dont. Another sign would be if those great powers start massive amounts of military aid, equipment, and technical advisors. Think USSR and th Arab states in the Cold War - sustained over time rather than a few cargo planes. Public alignment from one of the larger Gulf States is along another sign of a geopolitical shift.

Finally, don’t think nothing ever happens. Conflicts go quiet very fast and ignite just as fast. War is a great stimulus and national image booster. So an increase may not mean a full Ukraine War style conflict. It might be to prop up the current government it power. But that may hint at a larger pattern that’s forming. Not even related to Iran, but larger regional dynamics. Which I think we’ll see change again.

That’s all. Thanks for reading. I may do more deep dives, so let me know. This is a general overview.

Before then, if you have any questions or comments, feel free to comment and follow me:

Bluesky: pplsartofwar.bsky.social

Nice article. I wanted to ask if you think the USA will ever do a land invasion of the of Iran despite it mountainous terrain or keep using air campaigns.

There is indeed much theater to this conflict. However, we should consider that closure of commercial traffic thru Hormuz is a move that targets GCC and maybe EU, with collateral damage to oil importers around the world. It does not target US or Israel.

The analogy I'd consider is how the MSM discusses the possibility of a Taiwan showdown. Paints a picture of soaking wet PLA marines re-enacting D-day. The less fantastical scenario for that Island is a spectrum between civil war, and a selective blockade. Like what Yemen's Ansar Allah kept up in the Red Sea, in the face of decades of USN bravado about being the guarantor of global shipping. In the case of the Persian Gulf, USN already preemptively keeps prized targets out of the Gulf and at a substantial distance when action is imminent.

As for the theater, I have to think in this case it's part of an ongoing escalation process, rather than mere ritual. Think it's pretty well telegraphed by US and Israel that there will be future rounds.